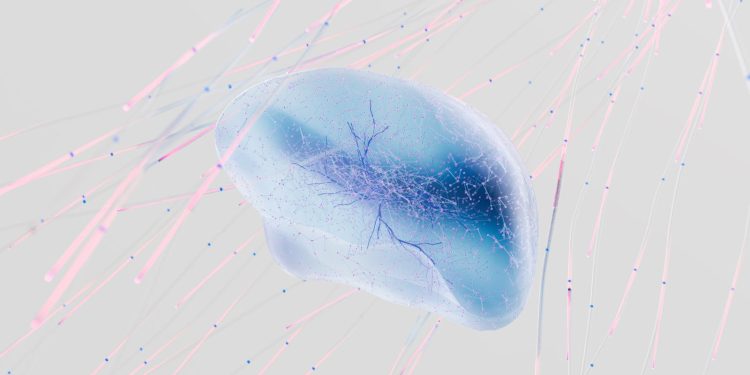

Addiction is a complex human experience that intertwines behavioral, psychological, and physiological factors. While it is easy to see addiction simply as repeated substance use, there is far more happening beneath the surface. Behind every substance dependence, there is a profound transformation occurring within the brain—a transformation that explains why addiction is not merely a matter of choice, but a profound struggle driven by changes in neurobiology. Understanding how substance use alters the brain can help us better grasp why addiction develops, why it is so difficult to overcome, and how it affects lives on multiple levels.

How Addiction Hijacks the Brain’s Reward System

To comprehend the psychology of addiction, it’s important to start with the brain’s reward system. Our brains are wired to help us survive by creating pleasurable feelings when we engage in activities necessary for survival, such as eating or socializing. This reward system relies heavily on a chemical known as dopamine, often referred to as the “feel-good” neurotransmitter. When we do something beneficial for survival, dopamine is released, creating a sense of pleasure that motivates us to repeat the activity.

Substances such as drugs and alcohol hack into this reward system by directly flooding the brain with unnaturally high levels of dopamine. The result? A euphoria far beyond what is typically experienced from natural rewards. This surge tricks the brain into perceiving that the substance is of critical importance. Over time, the brain starts to adjust by producing less dopamine on its own or reducing the number of dopamine receptors. As a result, activities that were once rewarding—like spending time with loved ones or enjoying hobbies—lose their allure, leaving the individual seeking out the substance just to feel “normal.”

This process, known as neuroadaptation, creates a powerful cycle in which the brain increasingly relies on substances to feel pleasure. The reward system is now hijacked, with the substance taking center stage in the individual’s life. The drive to use becomes compulsive, overpowering rational decision-making and often making it incredibly challenging to quit.

Tolerance and Dependence: The Brain’s Adjustment to Substance Use

As the brain adapts to continuous substance use, two related phenomena emerge: tolerance and dependence. Tolerance refers to the diminishing effect of a drug over time, which leads individuals to consume larger amounts to achieve the same high. This escalation of use creates a higher level of risk, both physically and psychologically.

Meanwhile, dependence emerges when the brain becomes so used to the presence of a substance that it can no longer function normally without it. Dependence involves changes in the brain’s chemistry that can lead to physical and psychological symptoms when the individual tries to stop using. The absence of the substance brings about withdrawal symptoms that can be incredibly painful—both physically and mentally—further reinforcing the cycle of addiction. Symptoms such as anxiety, depression, irritability, nausea, and tremors make quitting feel insurmountable without intervention.

The more an individual uses a substance, the more the brain changes to accommodate it. Over time, these changes can cause structural and functional shifts in various parts of the brain, particularly those involved in decision-making, memory, and impulse control. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for rational thinking and self-control, becomes impaired, which explains why many individuals struggling with addiction often find it difficult to make healthy choices, even when they are fully aware of the harmful consequences.

The Role of Memory and Learning in Addiction

The development of addiction is not just about chasing a pleasurable high; it also involves profound learning processes within the brain. Each time a person uses a substance, the brain records the experience, associating specific environmental cues—such as places, people, or emotional states—with the pleasure that the substance provides. This process is a form of classical conditioning, where external stimuli become tightly linked to drug use and the associated feelings of euphoria.

For instance, seeing a particular friend, driving by a favorite bar, or even experiencing stress can serve as powerful triggers that prompt cravings. These triggers are embedded in the brain’s limbic system, which is responsible for memory and emotional regulation. Even long after someone has stopped using the substance, these cues can evoke vivid memories and powerful cravings, sometimes leading to relapse. This is why addiction is considered a chronic condition; the brain’s associations with substance use can persist for years, if not for a lifetime.

The memory of using the substance and the associated pleasurable feeling is etched into the neural pathways of the brain, often lying dormant but ready to resurface when triggered. It’s this intertwining of memory, pleasure, and learning that makes addiction such a tenacious condition, capable of resurfacing even after long periods of abstinence.

Stress and Emotional Regulation in Addiction

Another key component in understanding addiction is the brain’s ability—or inability—to regulate emotions and cope with stress. Chronic substance use affects the brain’s hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is involved in the stress response. Over time, the individual’s ability to handle stress without substances becomes compromised. Small stressors that would have previously been manageable can now become overwhelming triggers for substance use.

Additionally, substances often become a form of self-medication. People might turn to drugs or alcohol to cope with underlying emotional issues such as anxiety, depression, or trauma. By artificially soothing these emotions, substances take on a powerful role, providing a temporary escape from psychological pain. Unfortunately, this escape is short-lived, and the cycle of dependence only exacerbates the emotional challenges it is meant to relieve.

Why Quitting Is So Difficult: The Cycle of Addiction

Given the significant alterations in the brain’s chemistry, quitting substance use is not simply a matter of willpower. The changes in the brain’s reward system, prefrontal cortex, and emotional regulation make it extremely challenging for individuals to break free from addiction. The compulsive nature of substance use, driven by cravings and the brain’s adaptation to the drug, is a hallmark of the disorder.

Cravings can be incredibly powerful, arising seemingly out of nowhere and consuming an individual’s thoughts. The brain’s reward system, once hijacked, creates intense urges that are difficult to ignore. These cravings, combined with withdrawal symptoms and impaired impulse control, explain why many people relapse even when they are committed to recovery.

Moreover, addiction is often accompanied by profound feelings of shame and guilt, which can prevent individuals from seeking help. The stigma surrounding addiction can lead people to isolate themselves, further perpetuating the cycle. It is important to recognize that addiction is a disease—one that changes the brain in ways that make self-control and abstinence difficult to achieve without support and intervention.

The Path to Recovery: Healing the Brain

Recovery from addiction involves both reversing and managing the brain changes caused by substance use. Although the alterations in the brain can be lasting, the concept of neuroplasticity offers hope. Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. In the context of addiction, this means that with time, therapy, and support, individuals can build new, healthier patterns of behavior and thought.

Behavioral therapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), play an essential role in addiction treatment. These therapies help individuals identify triggers, challenge harmful thought patterns, and develop coping strategies. By addressing the underlying thoughts and behaviors that contribute to substance use, individuals can gradually rewire their brain’s response to stress, emotions, and cravings.

Medications can also support recovery by reducing withdrawal symptoms and cravings, helping to stabilize the brain’s chemistry. Medications like methadone or buprenorphine for opioid addiction, and naltrexone for alcohol addiction, can make it easier for individuals to focus on the behavioral aspects of their recovery without being overwhelmed by the physical symptoms of withdrawal.

Social support is another critical factor in overcoming addiction. Engaging with supportive family members, peers, or support groups can provide a sense of community and accountability. Addiction often thrives in isolation, but recovery is nurtured through connection and understanding.

While the brain changes associated with addiction can make recovery a challenging journey, it is not impossible. Many individuals go on to live fulfilling, substance-free lives, even after years of struggling with addiction. The key lies in understanding that addiction is a disease—one that changes the brain, but also one that can be managed and treated with the right support, intervention, and dedication.

Moving Toward Empathy and Support

Understanding the psychology of addiction helps break down the stigma often associated with substance use. When we view addiction through the lens of brain changes and recognize that it involves complex interactions between neurobiology, environment, and behavior, we can foster greater empathy for those struggling. Addiction is not a moral failing or a simple lack of willpower; it is a condition that requires compassion, understanding, and comprehensive care.

The journey to recovery is often non-linear, with setbacks and progress happening in tandem. By offering non-judgmental support, improving access to treatment, and emphasizing the importance of mental health care, we can make a meaningful difference in the lives of individuals impacted by addiction. The brain is a resilient organ, capable of change and healing—and with the right resources, those affected by addiction can reclaim their lives, one day at a time.